A recurring discussion of writing and literary technique in television and film.

As Mad Men nears the close of its final season's first half, much of the discussion surrounding it has morphed into a rhetorical echo chamber: Does it deserve the hype? Is it really the canonical great some tout it to be, or are its many accolades a product of set design, nostalgia, and Matthew Weiner's "auteur" cult of personality? Ultimately, how it garnered its relevance is something we won't be able to grasp until we have the advantage of hindsight, but its indisputable mastery of scriptwriting craft emerges in the relationship it establishes between character and conflict.

Conflict is a complex term to pin down. In The Elements of Screenwriting: A Guide for Film and Television Writing, Irwin Blacker writes, "The conflict is the problem that the script is about." Alan Armer's definition in Writing the Screenplay is a bit knottier: "[Conflict] compels our attention. It draws us magnetically... Watch puppies at play. They fight with each other endlessly, growling, biting, attacking, lunging for the throat, retreating, and attacking again... For them, as for humans and other animals, conflict is play; play is conflict." Conflict is typically presented through an initial problem, one that directly complicates the protagonist's desires, hopes, needs, and fears. Young writers are often encouraged to consider the question, "Why today?" when sitting down to write their own stories. As storytellers, what are the reasons we choose a given moment to enter a story, as opposed to any other in the lives of our characters? Without this problem, it would seem that we (audiences, readers) enter the story at random, thereby neutering the plot's urgency. Crime shows and procedurals rely on the inherent moral binary for this problem. In fantasy and science fiction, a marked event usually sets the plot in motion; there's a cylon attack in Battlestar Galactica, Robert Baratheon asks Ned Stark to serve as Hand of the King in Game of Thrones. Dramatic realism, like Mad Men, must derive conflict from its characters.

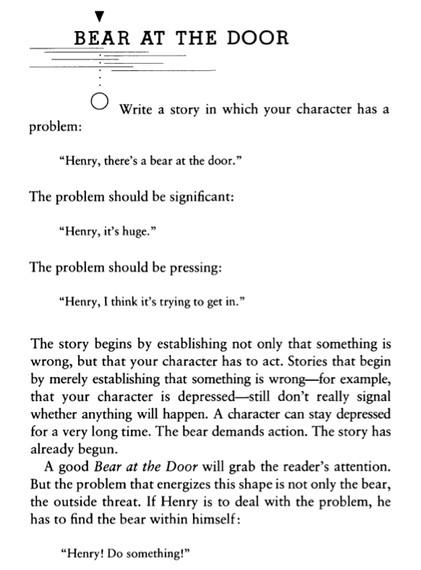

In Robert McKee's screenwriting guidebook, Story, he explains that, "The inciting incident, the first major event of telling, is the primary cause for all that follows... [it] radically upsets the balance of forces in the protagonist's life." Jerome Stern describes a similar event that he calls the "Bear at the Door":

![2014-05-11-Screenshot2014050814.59.14.png]()

In the pilot of Mad Men, we are introduced to the major players via two incidents: 1) Don's struggle to develop an effective campaign for Lucky Strike after new regulations have been placed on cigarette advertisements, and 2) Peggy's first day working at Sterling Cooper (the introductory ritual doubling as character exposition for the rest of the bunch). These inciting incidents are structural stand-ins: They usher us into the episode, contextualizing the characters in the world, but do little work to otherwise present a long-form conflict. The episode relies on insinuation to establish tonal gravitas; in retrospective viewings, one notices many clues of what's to come. Joan greets Roger with a touch of affection that he slights, Don stuffs "his" Purple Heart in his desk drawer, Salvatore drops repeated hints regarding his latent homosexuality. These components aren't being obviously thrust against each other; many take seasons to materialize into plot lines, and others never do.

Throughout Mad Men's run, many have commented on its "slow burn" progression, and some have cited its soapiness as a shortcoming. There's a separate discussion to be had about the merits of soap opera tropes and their absorption into the contemporary media landscape, but it is Weiner's specific and successful incorporation of these tropes that distinguishes Mad Men from other heavy-hitters such as network counterpart Breaking Bad. What has taken place is a reversal of its target audience's expectations: rather than working from a definitive inciting incident (Walt's cancer diagnosis) that requires immediate action (cooking meth to generate quick money to leave behind for his family), we find that, as we progress, we stumble upon what would otherwise have taken the form of inciting incidents -- many occurring in the latter seasons of the show's run. More than any before it, this season most directly addresses "Why today?" We find many of the characters finally confronting their respective bears, or dealing with the aftermath of these confrontations, which, for many, rely on Los Angeles as a locus of physical and metaphorical change. Don, on forced leave, wants his job back in a way he doesn't seem to extend to his marriage with Megan, who has meanwhile established herself and her career out West. Peggy and Ted work on opposite ends of the country in the wake of their failed romance, and Pete's relocation has induced significant shifts in lifestyle. In a space where we should most acutely experience the distancing effects of denouement, we find instead an increased closeness through the chaotic ramping-up of movement and transformation.

In Bird by Bird: Some Instructions on Writing and Life, Anne Lamott explains, "Plot grows out of character. If you focus on who the people in your story are, if you sit and write about two people you know and are getting to know better day by day, something is bound to happen." Our purpose in watching Mad Men is not to see plot points resolved, but to witness its characters grow without focusing on an end point. Whatever one may argue about the show's realism or verisimilitude, where it does imitate the rhythms of reality is in its handling of human problems, which are rarely (if ever) structured around neat arcs. Our identities form around our reactions to the circumstances of our lives -- teaching, confirming, and undermining who we believe we are or want to be -- and we can share these lessons through narrative. There's a trove of adages about the importance of valuing the journey over the destination, and in directing our eyes toward the humanity of its characters, that's precisely what Mad Men shows us how to do.

As Mad Men nears the close of its final season's first half, much of the discussion surrounding it has morphed into a rhetorical echo chamber: Does it deserve the hype? Is it really the canonical great some tout it to be, or are its many accolades a product of set design, nostalgia, and Matthew Weiner's "auteur" cult of personality? Ultimately, how it garnered its relevance is something we won't be able to grasp until we have the advantage of hindsight, but its indisputable mastery of scriptwriting craft emerges in the relationship it establishes between character and conflict.

Conflict is a complex term to pin down. In The Elements of Screenwriting: A Guide for Film and Television Writing, Irwin Blacker writes, "The conflict is the problem that the script is about." Alan Armer's definition in Writing the Screenplay is a bit knottier: "[Conflict] compels our attention. It draws us magnetically... Watch puppies at play. They fight with each other endlessly, growling, biting, attacking, lunging for the throat, retreating, and attacking again... For them, as for humans and other animals, conflict is play; play is conflict." Conflict is typically presented through an initial problem, one that directly complicates the protagonist's desires, hopes, needs, and fears. Young writers are often encouraged to consider the question, "Why today?" when sitting down to write their own stories. As storytellers, what are the reasons we choose a given moment to enter a story, as opposed to any other in the lives of our characters? Without this problem, it would seem that we (audiences, readers) enter the story at random, thereby neutering the plot's urgency. Crime shows and procedurals rely on the inherent moral binary for this problem. In fantasy and science fiction, a marked event usually sets the plot in motion; there's a cylon attack in Battlestar Galactica, Robert Baratheon asks Ned Stark to serve as Hand of the King in Game of Thrones. Dramatic realism, like Mad Men, must derive conflict from its characters.

In Robert McKee's screenwriting guidebook, Story, he explains that, "The inciting incident, the first major event of telling, is the primary cause for all that follows... [it] radically upsets the balance of forces in the protagonist's life." Jerome Stern describes a similar event that he calls the "Bear at the Door":

In the pilot of Mad Men, we are introduced to the major players via two incidents: 1) Don's struggle to develop an effective campaign for Lucky Strike after new regulations have been placed on cigarette advertisements, and 2) Peggy's first day working at Sterling Cooper (the introductory ritual doubling as character exposition for the rest of the bunch). These inciting incidents are structural stand-ins: They usher us into the episode, contextualizing the characters in the world, but do little work to otherwise present a long-form conflict. The episode relies on insinuation to establish tonal gravitas; in retrospective viewings, one notices many clues of what's to come. Joan greets Roger with a touch of affection that he slights, Don stuffs "his" Purple Heart in his desk drawer, Salvatore drops repeated hints regarding his latent homosexuality. These components aren't being obviously thrust against each other; many take seasons to materialize into plot lines, and others never do.

Throughout Mad Men's run, many have commented on its "slow burn" progression, and some have cited its soapiness as a shortcoming. There's a separate discussion to be had about the merits of soap opera tropes and their absorption into the contemporary media landscape, but it is Weiner's specific and successful incorporation of these tropes that distinguishes Mad Men from other heavy-hitters such as network counterpart Breaking Bad. What has taken place is a reversal of its target audience's expectations: rather than working from a definitive inciting incident (Walt's cancer diagnosis) that requires immediate action (cooking meth to generate quick money to leave behind for his family), we find that, as we progress, we stumble upon what would otherwise have taken the form of inciting incidents -- many occurring in the latter seasons of the show's run. More than any before it, this season most directly addresses "Why today?" We find many of the characters finally confronting their respective bears, or dealing with the aftermath of these confrontations, which, for many, rely on Los Angeles as a locus of physical and metaphorical change. Don, on forced leave, wants his job back in a way he doesn't seem to extend to his marriage with Megan, who has meanwhile established herself and her career out West. Peggy and Ted work on opposite ends of the country in the wake of their failed romance, and Pete's relocation has induced significant shifts in lifestyle. In a space where we should most acutely experience the distancing effects of denouement, we find instead an increased closeness through the chaotic ramping-up of movement and transformation.

In Bird by Bird: Some Instructions on Writing and Life, Anne Lamott explains, "Plot grows out of character. If you focus on who the people in your story are, if you sit and write about two people you know and are getting to know better day by day, something is bound to happen." Our purpose in watching Mad Men is not to see plot points resolved, but to witness its characters grow without focusing on an end point. Whatever one may argue about the show's realism or verisimilitude, where it does imitate the rhythms of reality is in its handling of human problems, which are rarely (if ever) structured around neat arcs. Our identities form around our reactions to the circumstances of our lives -- teaching, confirming, and undermining who we believe we are or want to be -- and we can share these lessons through narrative. There's a trove of adages about the importance of valuing the journey over the destination, and in directing our eyes toward the humanity of its characters, that's precisely what Mad Men shows us how to do.