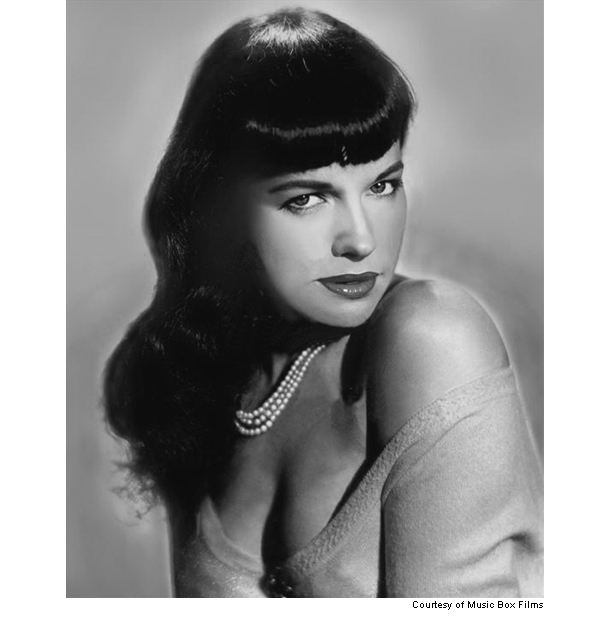

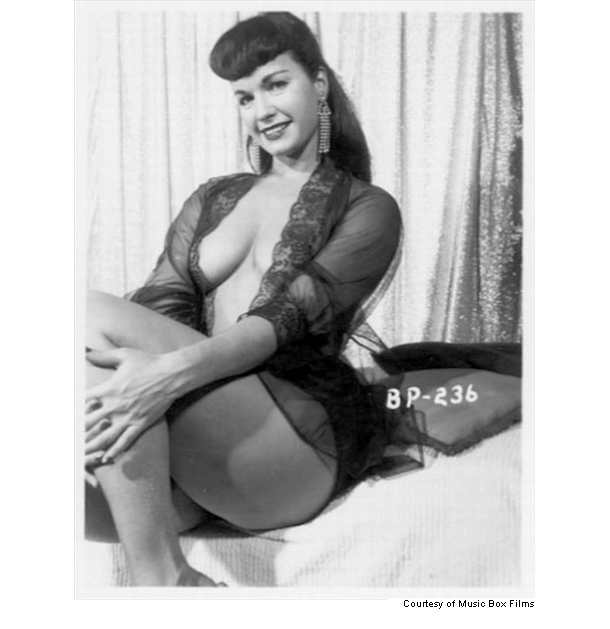

Few swimsuit models have set the culture on fire quite like Bettie Page.

In the early 1950s, when bikinis could not be bought in stores and photographers could be arrested for sending nude pics through the mail, Page posed for thousands of bondage and spanking photos. Her image was featured in a widely distributed series of pin-up calendars, drawing the ire of conservative Christians and triggering a Congressional investigation into the spread of pornography.

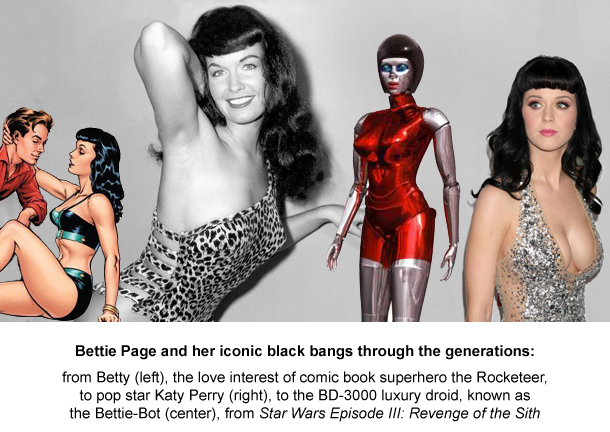

Today, more than half a century later, her image is everywhere: in our movies and music, our comics and science fiction, our fashion and our literature. Who was this woman who captured America's imagination and touched so many corners of our culture? Mark Mori needed to find out.

![]() The acclaimed documentarian might be the last person you'd expect to investigate a 1950's sex icon. Mori earned an Oscar nomination for his eye-opening examination of the environmental damage caused by a nuclear bomb factory in South Carolina; he won an Emmy for his reporting on the Kent State massacre. But Page soon proved more fascinating than any political scandal. Mori became entranced, devoting 16 years to tracing the winding path of Page's life: from sexual abuse to the orphanage, pinup stardom to being institutionalized for schizophrenia, before an unexpected burst of fame and wealth, then death.

The acclaimed documentarian might be the last person you'd expect to investigate a 1950's sex icon. Mori earned an Oscar nomination for his eye-opening examination of the environmental damage caused by a nuclear bomb factory in South Carolina; he won an Emmy for his reporting on the Kent State massacre. But Page soon proved more fascinating than any political scandal. Mori became entranced, devoting 16 years to tracing the winding path of Page's life: from sexual abuse to the orphanage, pinup stardom to being institutionalized for schizophrenia, before an unexpected burst of fame and wealth, then death.

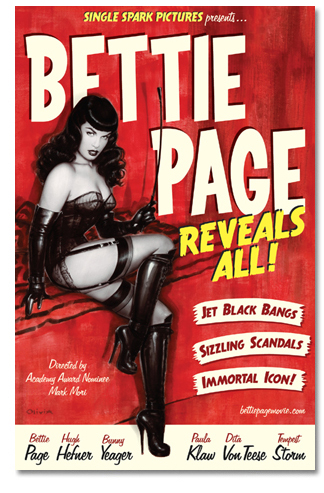

Mori's film, Bettie Page Reveals All, has just been released on Netflix, Vimeo and Amazon Instant Video. The film features interviews with Playboy founder Hugh Hefner, photographer Bunny Yeager and narration from Page herself, drawn from extensive interviews she recorded with Mori before her death from pneumonia in 2008.

Mori spoke with me about working with Page, her brilliance and madness, and the twist of fate that brought them together.

![]()

Mori: I had seen her photos of her years ago but never thought much about them. I certainly hadn't thought about making a movie about her. Then my attorney showed me this book, Bettie Page: The Life of a Pin-Up Legend. I can't explain why, but it just struck me. There was something magical in her image. He said, "You want to meet her?" Hugh Hefner had gotten Bettie a lawyer, so she could finally profit from all the people using her image. My lawyer, he was Bettie's lawyer's lawyer. You could say I was in the right place at the right time.

Kors: You went to see her.

Mori: I did. At this point, she had completely retreated from society. You could count the number of people she had contact with on two hands. I drove out to meet her at this halfway house run by Patton State Hospital, which was helping her transition back into regular society. She was in her 70's and didn't have that 36-24-36 body. But she had the same smile. And those same bangs. We just hit it off.

Kors: How often would you see her?

Mori: I took her to lunch periodically, over the course of several years. She'd tell me about her childhood, her marriages, tell me crazy stories about those bondage and fetish shoots. I started noticing her image around town and recognizing her influence everywhere. Bettie is like this underground river in our culture, influencing everything from punk rock to Fifty Shades of Grey. You have acclaimed painter Robert Blue making paintings of her that are 10 feet tall and displayed in top galleries, a high-culture celebration of a woman whose career played out entirely on the fringes. She left modeling and acting in 1957 and never starred in a mainstream movie.

![]()

Kors: So why the lasting resonance?

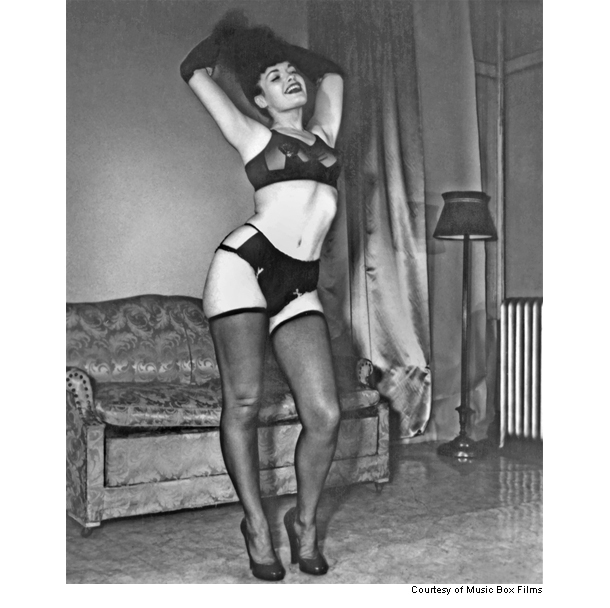

Mori: That's the key question of the movie. I think it was her attitude. Bettie reveled in the joy of being female. You can see that in all of her photos: the joy she takes in her body, in her sexuality. Compare that to so many of today's models who come across as cold and distant. Bettie was accessible and human. She paved the way for a whole generation of women to accept their bodies and embrace their sexuality. It's ironic because in the 1950s, her photos were seen as purely exploitative. Now so many women revel in Bettie. They find liberation in her.

Kors: You presented to her the idea of making a movie about her life.

Mori: I did. She was completely indifferent to it. She couldn't understand why anyone would be interested. "That was two lifetimes ago," she said. [Mori laughs.] You know how a lot of movie stars can't let go? She never looked back. And she could not understand Hollywood people who did, who latched onto their image and rode it as far as it would take them. That was part of her charm: there was no artifice, no guile. As far as she was concerned, with her modeling, she was just making a living.

Kors: She didn't hunger for fame.

Mori: [Mori laughs.] No, she was completely indifferent to it. If anything, she wanted to maintain her anonymity.

![]()

Kors: Bettie narrates the movie. But one of her conditions for doing the film was that she remain off-camera.

Mori: No. It wasn't a condition. But she strongly preferred to be off-camera. She didn't like the way she looked now, and she wanted to be remembered as she was. I asked her a number of times to reconsider. And there were a few photos of her in her old age that I could have used. But in the end, I wanted to respect her wishes.

Kors: Her disinterest in going viral, that's part of who she was.

Mori: There's this idea that pervades the culture now of "Wow, I can get on camera. I can be noticed!" That meant nothing to her. Even in the '50s, when she was doing bondage photo shoots, she never dressed up off-camera. She'd walk down Fifth Avenue wearing plain, flannel shirts. You would never have known she was a model until she got to the studio and slipped on her gear.

![]() Kors: There's a delightful bluntness to Bettie's narration. She says things like, "Mmm, he was quite a man" and "Oh, he was a great lover."

Kors: There's a delightful bluntness to Bettie's narration. She says things like, "Mmm, he was quite a man" and "Oh, he was a great lover."

Mori: [Mori laughs.] Yes, there was real nonchalance about her. That really struck me. For someone so private, who did not want to be on camera, she had no trouble talking openly and honestly about her romances. She took real joy in her sexuality and in her beauty, without being stuck up about it. She was the girl next door who was up for anything. And yet she was also a born-again Christian who went through a crisis of conscience, questioning whether her videos and photos were the right thing to do.

Kors: There's something very American about her story.

Mori: I agree. I think she's the embodiment of some important contradictions in this country, these dueling forces in our culture: sexual freedom versus right-wing, fundamentalist sexual repression. It's an ongoing conflict. Did you know that our YouTube channel promoting the film was censored because in one of the party scenes, you could see one girl's pantyhose? I knew that we couldn't post any nudity. Apparently we can't show pantyhose either. These forces in our country, they're constantly at war.

![]()

Kors: Do you see the film as a political film then?

Mori: Partly it is. But it's also great fun. Bettie has broad appeal. Guys revel in her beauty. Women respect her agency, not just posing for photos but designing the clothes and styling her own hair and makeup. And to the gay community and tattoo community, she's like a patron saint, an icon of liberation and free expression.

Kors: The film explores how Bettie affected the sexual revolution. I must have missed those years, so fill me in.

Mori: Oh, I can tell you about the sexual revolution because I was there. [Mori laughs.] In the '50s, America was very repressed. During World War II, women had moved into the factories, and now in the '50s, they were being stuffed back into being housewives. Then came the Kinsey Report and then, in the '60s, the invention of the pill. Hugh Hefner successfully sued to force the post office to deliver naked pictures. Before that, if a publication had nudity in it, you couldn't even send it through private mail. Society shifted, and Bettie, her photos were fun. They had no guilt attached to them. She brought fetish out of the closet. Of course she wasn't trying to do that. That's what makes her story so remarkable: she had a monumental impact on so many realms of America, and she wasn't trying to do any of it.

![]()

Kors: She speaks with disturbing honesty about her childhood. How her father pressed and pressed, and finally she allowed him to touch her, so she could get money from him to go to the movies. How she never let him penetrate her the way he did with her sisters.

Mori: Yeah, her father was a sick, twisted criminal. A lot of her problems, obviously, trace back to her being molested by her father. One of the stories I had to cut from the finished film was that her father also got a very young girl, their neighbor's daughter, pregnant. The neighbor then came chasing after him with a shotgun.

Kors: Jeez.

Mori: Her childhood was awful, and it wasn't just her father. She was completely unloved by her mother. Bettie told me that her mother only hugged her once, that she made it clear that she did not want her.

Kors: Eventually Bettie's mother did leave her abusive husband.

Mori: She did. Which left her mother with a third-grade education and six kids to feed. This was 1934. Bettie was 11. There was no welfare, no safety net back then. Which is why so many women of that era in her mother's situation stayed with their husbands and allowed them to sexually abuse the children. Bettie's mother decided instead to leave the marriage and get a job.

Kors: That's why Bettie and her siblings were sent to an orphanage.

Mori: Yes.

![]()

Kors: After going through all that together, you'd think that she and her siblings would be close. But I got the sense that they weren't.

Mori: No, they weren't. I talked with her brother Jack on the phone, but her sisters weren't interested in speaking with me. Her sisters did occasionally visit her at the halfway house. Bettie said that one sister was never mentally right after the abuse. And she resented Bettie's talking about what they went through.

Kors: What was Bettie's official diagnosis?

Mori: She was diagnosed as a paranoid schizophrenic.

Kors: This was after she stabbed her landlord and held her husband and his children hostage, at knifepoint, and told them not to take their eyes off the image of Jesus on the wall.

Mori: Yes. And yet many of the men I interviewed, they were still pining for her. Like her ex-husband, Harry Lear, who was just a normal guy who worked for Bell Telephone. You can see in the movie, he was still in love with her. There were photographers and designers. To all these men, she was the one who got away.

Kors: She speaks very little in the film about her violent break.

Mori: Yes, that was the one area where I could not get her to open up. She spoke with me about the mental institution. But the knife incidents, what got her to the institution, she wouldn't go there. It was like her brain still couldn't process those moments.

![]()

Kors: She also doesn't quite explain why, in the late '50s, at the height of her fame, she walked away from her career. She describes one shoot where the photographers got her to drink, and when she got tipsy, they took photos that were a bit more revealing than she would have liked. But that was it? One bad shoot and she walks away?

Mori: No, that wasn't it. She felt that she was getting too old to model. She was 34 passing for 22. Her image had become ubiquitous: on magazines, posters and calendars. And she was deeply shaken by the Kefauver hearings. [In 1955, Senator Estes Kefauver held hearings targeting Page and other "obscenity producers." The senator called Page and photographer Irving Klaw to testify before the committee.] It was a lot to handle.

Kors: Bettie died in 2008, after contracting pneumonia. How did you leave things with her?

Mori: I came to see her in the hospital. She had had a stroke and had to struggle to get words out. I said, "I love you, Bettie." And she struggled to say, "I love you too." In those final years she didn't have many friends. She wasn't going out to the movies with anyone or going shopping. In the end, I considered myself a friend because I fully appreciated who she was.

Follow Joshua Kors on Facebook at www.facebook.com/joshua.kors

Follow Joshua Kors on Twitter at www.twitter.com/joshuakors

In the early 1950s, when bikinis could not be bought in stores and photographers could be arrested for sending nude pics through the mail, Page posed for thousands of bondage and spanking photos. Her image was featured in a widely distributed series of pin-up calendars, drawing the ire of conservative Christians and triggering a Congressional investigation into the spread of pornography.

Today, more than half a century later, her image is everywhere: in our movies and music, our comics and science fiction, our fashion and our literature. Who was this woman who captured America's imagination and touched so many corners of our culture? Mark Mori needed to find out.

The acclaimed documentarian might be the last person you'd expect to investigate a 1950's sex icon. Mori earned an Oscar nomination for his eye-opening examination of the environmental damage caused by a nuclear bomb factory in South Carolina; he won an Emmy for his reporting on the Kent State massacre. But Page soon proved more fascinating than any political scandal. Mori became entranced, devoting 16 years to tracing the winding path of Page's life: from sexual abuse to the orphanage, pinup stardom to being institutionalized for schizophrenia, before an unexpected burst of fame and wealth, then death.

The acclaimed documentarian might be the last person you'd expect to investigate a 1950's sex icon. Mori earned an Oscar nomination for his eye-opening examination of the environmental damage caused by a nuclear bomb factory in South Carolina; he won an Emmy for his reporting on the Kent State massacre. But Page soon proved more fascinating than any political scandal. Mori became entranced, devoting 16 years to tracing the winding path of Page's life: from sexual abuse to the orphanage, pinup stardom to being institutionalized for schizophrenia, before an unexpected burst of fame and wealth, then death.Mori's film, Bettie Page Reveals All, has just been released on Netflix, Vimeo and Amazon Instant Video. The film features interviews with Playboy founder Hugh Hefner, photographer Bunny Yeager and narration from Page herself, drawn from extensive interviews she recorded with Mori before her death from pneumonia in 2008.

Mori spoke with me about working with Page, her brilliance and madness, and the twist of fate that brought them together.

Mori: I had seen her photos of her years ago but never thought much about them. I certainly hadn't thought about making a movie about her. Then my attorney showed me this book, Bettie Page: The Life of a Pin-Up Legend. I can't explain why, but it just struck me. There was something magical in her image. He said, "You want to meet her?" Hugh Hefner had gotten Bettie a lawyer, so she could finally profit from all the people using her image. My lawyer, he was Bettie's lawyer's lawyer. You could say I was in the right place at the right time.

Kors: You went to see her.

Mori: I did. At this point, she had completely retreated from society. You could count the number of people she had contact with on two hands. I drove out to meet her at this halfway house run by Patton State Hospital, which was helping her transition back into regular society. She was in her 70's and didn't have that 36-24-36 body. But she had the same smile. And those same bangs. We just hit it off.

Kors: How often would you see her?

Mori: I took her to lunch periodically, over the course of several years. She'd tell me about her childhood, her marriages, tell me crazy stories about those bondage and fetish shoots. I started noticing her image around town and recognizing her influence everywhere. Bettie is like this underground river in our culture, influencing everything from punk rock to Fifty Shades of Grey. You have acclaimed painter Robert Blue making paintings of her that are 10 feet tall and displayed in top galleries, a high-culture celebration of a woman whose career played out entirely on the fringes. She left modeling and acting in 1957 and never starred in a mainstream movie.

Kors: So why the lasting resonance?

Mori: That's the key question of the movie. I think it was her attitude. Bettie reveled in the joy of being female. You can see that in all of her photos: the joy she takes in her body, in her sexuality. Compare that to so many of today's models who come across as cold and distant. Bettie was accessible and human. She paved the way for a whole generation of women to accept their bodies and embrace their sexuality. It's ironic because in the 1950s, her photos were seen as purely exploitative. Now so many women revel in Bettie. They find liberation in her.

Kors: You presented to her the idea of making a movie about her life.

Mori: I did. She was completely indifferent to it. She couldn't understand why anyone would be interested. "That was two lifetimes ago," she said. [Mori laughs.] You know how a lot of movie stars can't let go? She never looked back. And she could not understand Hollywood people who did, who latched onto their image and rode it as far as it would take them. That was part of her charm: there was no artifice, no guile. As far as she was concerned, with her modeling, she was just making a living.

Kors: She didn't hunger for fame.

Mori: [Mori laughs.] No, she was completely indifferent to it. If anything, she wanted to maintain her anonymity.

Kors: Bettie narrates the movie. But one of her conditions for doing the film was that she remain off-camera.

Mori: No. It wasn't a condition. But she strongly preferred to be off-camera. She didn't like the way she looked now, and she wanted to be remembered as she was. I asked her a number of times to reconsider. And there were a few photos of her in her old age that I could have used. But in the end, I wanted to respect her wishes.

Kors: Her disinterest in going viral, that's part of who she was.

Mori: There's this idea that pervades the culture now of "Wow, I can get on camera. I can be noticed!" That meant nothing to her. Even in the '50s, when she was doing bondage photo shoots, she never dressed up off-camera. She'd walk down Fifth Avenue wearing plain, flannel shirts. You would never have known she was a model until she got to the studio and slipped on her gear.

Kors: There's a delightful bluntness to Bettie's narration. She says things like, "Mmm, he was quite a man" and "Oh, he was a great lover."

Kors: There's a delightful bluntness to Bettie's narration. She says things like, "Mmm, he was quite a man" and "Oh, he was a great lover."Mori: [Mori laughs.] Yes, there was real nonchalance about her. That really struck me. For someone so private, who did not want to be on camera, she had no trouble talking openly and honestly about her romances. She took real joy in her sexuality and in her beauty, without being stuck up about it. She was the girl next door who was up for anything. And yet she was also a born-again Christian who went through a crisis of conscience, questioning whether her videos and photos were the right thing to do.

Kors: There's something very American about her story.

Mori: I agree. I think she's the embodiment of some important contradictions in this country, these dueling forces in our culture: sexual freedom versus right-wing, fundamentalist sexual repression. It's an ongoing conflict. Did you know that our YouTube channel promoting the film was censored because in one of the party scenes, you could see one girl's pantyhose? I knew that we couldn't post any nudity. Apparently we can't show pantyhose either. These forces in our country, they're constantly at war.

Kors: Do you see the film as a political film then?

Mori: Partly it is. But it's also great fun. Bettie has broad appeal. Guys revel in her beauty. Women respect her agency, not just posing for photos but designing the clothes and styling her own hair and makeup. And to the gay community and tattoo community, she's like a patron saint, an icon of liberation and free expression.

Kors: The film explores how Bettie affected the sexual revolution. I must have missed those years, so fill me in.

Mori: Oh, I can tell you about the sexual revolution because I was there. [Mori laughs.] In the '50s, America was very repressed. During World War II, women had moved into the factories, and now in the '50s, they were being stuffed back into being housewives. Then came the Kinsey Report and then, in the '60s, the invention of the pill. Hugh Hefner successfully sued to force the post office to deliver naked pictures. Before that, if a publication had nudity in it, you couldn't even send it through private mail. Society shifted, and Bettie, her photos were fun. They had no guilt attached to them. She brought fetish out of the closet. Of course she wasn't trying to do that. That's what makes her story so remarkable: she had a monumental impact on so many realms of America, and she wasn't trying to do any of it.

Kors: She speaks with disturbing honesty about her childhood. How her father pressed and pressed, and finally she allowed him to touch her, so she could get money from him to go to the movies. How she never let him penetrate her the way he did with her sisters.

Mori: Yeah, her father was a sick, twisted criminal. A lot of her problems, obviously, trace back to her being molested by her father. One of the stories I had to cut from the finished film was that her father also got a very young girl, their neighbor's daughter, pregnant. The neighbor then came chasing after him with a shotgun.

Kors: Jeez.

Mori: Her childhood was awful, and it wasn't just her father. She was completely unloved by her mother. Bettie told me that her mother only hugged her once, that she made it clear that she did not want her.

Kors: Eventually Bettie's mother did leave her abusive husband.

Mori: She did. Which left her mother with a third-grade education and six kids to feed. This was 1934. Bettie was 11. There was no welfare, no safety net back then. Which is why so many women of that era in her mother's situation stayed with their husbands and allowed them to sexually abuse the children. Bettie's mother decided instead to leave the marriage and get a job.

Kors: That's why Bettie and her siblings were sent to an orphanage.

Mori: Yes.

Kors: After going through all that together, you'd think that she and her siblings would be close. But I got the sense that they weren't.

Mori: No, they weren't. I talked with her brother Jack on the phone, but her sisters weren't interested in speaking with me. Her sisters did occasionally visit her at the halfway house. Bettie said that one sister was never mentally right after the abuse. And she resented Bettie's talking about what they went through.

Kors: What was Bettie's official diagnosis?

Mori: She was diagnosed as a paranoid schizophrenic.

Kors: This was after she stabbed her landlord and held her husband and his children hostage, at knifepoint, and told them not to take their eyes off the image of Jesus on the wall.

Mori: Yes. And yet many of the men I interviewed, they were still pining for her. Like her ex-husband, Harry Lear, who was just a normal guy who worked for Bell Telephone. You can see in the movie, he was still in love with her. There were photographers and designers. To all these men, she was the one who got away.

Kors: She speaks very little in the film about her violent break.

Mori: Yes, that was the one area where I could not get her to open up. She spoke with me about the mental institution. But the knife incidents, what got her to the institution, she wouldn't go there. It was like her brain still couldn't process those moments.

Kors: She also doesn't quite explain why, in the late '50s, at the height of her fame, she walked away from her career. She describes one shoot where the photographers got her to drink, and when she got tipsy, they took photos that were a bit more revealing than she would have liked. But that was it? One bad shoot and she walks away?

Mori: No, that wasn't it. She felt that she was getting too old to model. She was 34 passing for 22. Her image had become ubiquitous: on magazines, posters and calendars. And she was deeply shaken by the Kefauver hearings. [In 1955, Senator Estes Kefauver held hearings targeting Page and other "obscenity producers." The senator called Page and photographer Irving Klaw to testify before the committee.] It was a lot to handle.

Kors: Bettie died in 2008, after contracting pneumonia. How did you leave things with her?

Mori: I came to see her in the hospital. She had had a stroke and had to struggle to get words out. I said, "I love you, Bettie." And she struggled to say, "I love you too." In those final years she didn't have many friends. She wasn't going out to the movies with anyone or going shopping. In the end, I considered myself a friend because I fully appreciated who she was.

Follow Joshua Kors on Facebook at www.facebook.com/joshua.kors

Follow Joshua Kors on Twitter at www.twitter.com/joshuakors