If you know Victor Hugo's name it's probably as the author of Les Misérables and The Hunchback of Notre-Dame but the character whose features have made the biggest mark on popular culture is the hero of a lesser-known novel. If you're a hardcore comic book fan you may already know that the inspiration for Batman's nemesis, the Joker, was a poster featuring Conrad Veidt as the disfigured hero of the1928 silent film, "The Man Who Laughs." The psychopathic Joker has carved a path of bloody mayhem through the city of Gotham in comics and movies for almost 75 years since his first appearance in Batman #1 and it was the Joker who indirectly led me to the novel by Victor Hugo that was the original source for the movie.

In 2011 I was writing a story for DC's Batman and Robin comic book, set in Paris and featuring a French version of the Joker, whose father was a fan of Victor Hugo's work and chose to mutilate his son's face in homage to the lead character of The Man Who Laughs. I only had a vague sense of the plot of the novel at the time so it made sense to get hold of a copy. Most editions seemed to be out of print but I finally tracked one down on Amazon and a couple of days later a hefty tome arrived in the post.

The Man Who Laughs is not an easy read. It was written late in Victor Hugo's career when he was living in exile on Guernsey, and his contemporaries dismissed it as an inferior work. It's certainly a pretty turgid read, crammed with long-winded exposition and with a non-linear timeline that annoyingly gives away all the best plot twists too soon. I felt like scrawling "Spoiler Alert!" in the margins when I wasn't skipping the endless inventories of titles, ranks and possessions of the English aristocracy. But while I was often infuriated by the book's structure I found myself gripped by the underlying story. Here was a truly enthralling tale of love and humanity, of ordinary people struggling to survive in an unjust and unequal society. At it's core is the story of a young man who is kidnapped, mutilated and sold to travelling entertainers, yet who retains his integrity and his dignity through the love of his adoptive 'family', the eccentric philosopher Ursus, his pet wolf Homo and the beautiful blind girl, Dea.

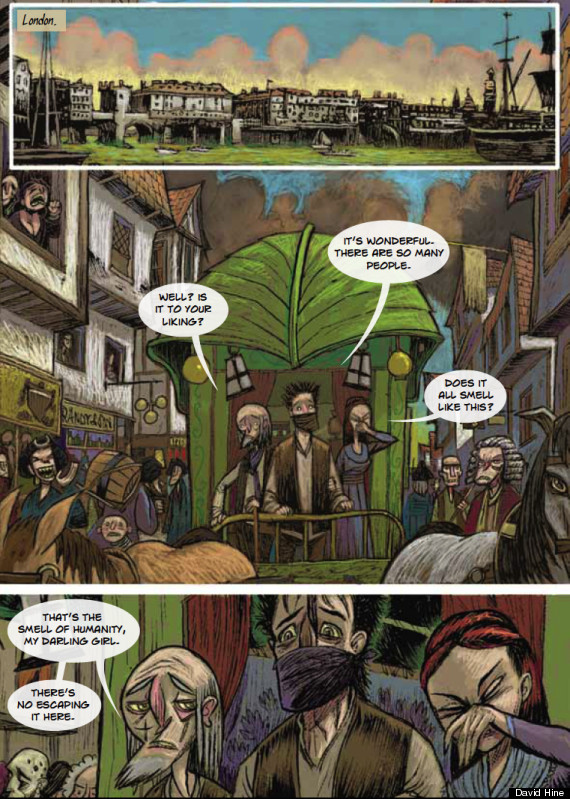

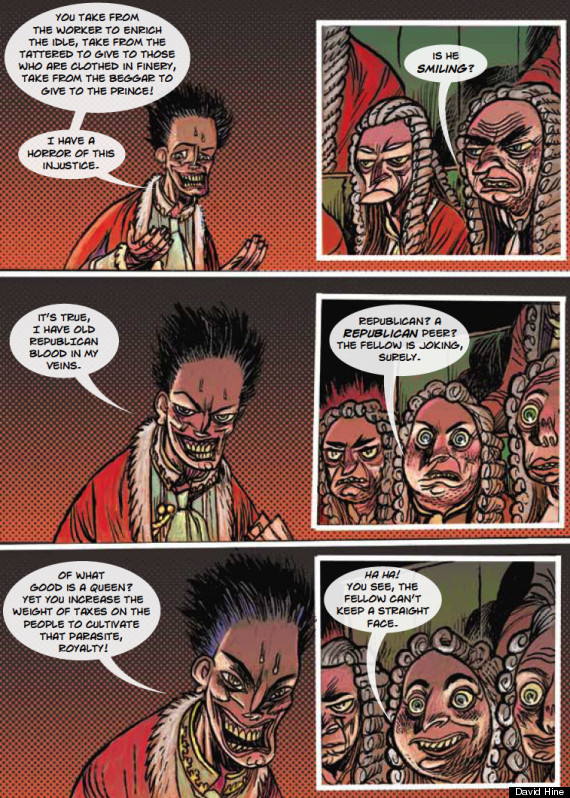

The book is a political thriller, a "whodunit" mystery, a love story and a scathing attack on injustice and social inequality. When, near the story's climax, Gwynplaine addresses the House of Lords, his bitter rebuke of the élite who govern Britain rings as true today as it did then. He launches an assault on this tiny minority who posses most of the wealth and land and all of the power, exploiting the labor of the poor in order to live in luxury, raising taxes to support a parasitic monarchy and treating the common people with contempt. Gwynplaine holds himself up as a symbol of abuse. "I represent humanity, such as its masters have made it. Mankind is mutilated." And he has a warning that one day the people will rise up and restore the Republic that briefly existed under Cromwell.

Victor Hugo would no doubt be appalled that modern Britain remains a monarchy and even more so that the inequality he railed against is still there. In 2014 the richest 1% own as much as the poorest 55% and the wealth gap is growing. That makes The Man Who Laughs as pertinent to modern readers as it was in 1869 when it was first published and the elements of the book that provoked ridicule when it was first published no longer seem as absurd. The grotesque and theatrical settings and characters are more familiar to us today after a century that gave us surrealism, expressionist cinema and the modern gothic imagery of TV shows like Twin Peaks and indeed, the more recent Batman films.

Hugo was an accomplished and visionary artist in his own right and many of the scenes in the book are so well visualized that they played out in my head like a movie. As I read the early scene where the young Gwynplaine is abandoned to walk barefoot through a snowstorm, encountering first a rotting corpse hanging from a gibbet and then, having never been shown a single act of kindness, risking his life to save a child who is even more helpless than himself, I knew I had to turn this into a graphic novel, to bring that story to life and introduce it to a new audience.

A graphic novel is, in many ways, superior to cinema as an art form. Watching a movie is a largely passive entertainment, where sounds and images flow at their own speed. Reading a graphic novel is a much more interactive and intimate experience. The words and images are printed, static, to be read and absorbed at the readers own pace. You can go back and re-read dialogue or pause and study a picture to appreciate the nuances that you didn't pick up first time around.

As a writer I have to know when to shut up and let the pictures do the talking. My collaborator, the artist Mark Stafford has done a real service to the book and I'm sure Victor Hugo would have approved of the way Mark has gotten to the heart of Gwynplaine and the cast of heroes, villains and those 'common' people who are, for the most part neither hero nor villain. If we have done our job right, they will make you laugh and make you weep... and maybe, unless you happen to be part of that privileged 1%, also provoke a little righteous anger.

Read an excerpt from The Man Who Laughs below:

![hine 1]()

![hine 2]()

![hine 3]()

![hine 4]()

David Hine is the illustrator of a graphic novel adaptation of Victor Hugo's The Man Who Laughs.

In 2011 I was writing a story for DC's Batman and Robin comic book, set in Paris and featuring a French version of the Joker, whose father was a fan of Victor Hugo's work and chose to mutilate his son's face in homage to the lead character of The Man Who Laughs. I only had a vague sense of the plot of the novel at the time so it made sense to get hold of a copy. Most editions seemed to be out of print but I finally tracked one down on Amazon and a couple of days later a hefty tome arrived in the post.

The Man Who Laughs is not an easy read. It was written late in Victor Hugo's career when he was living in exile on Guernsey, and his contemporaries dismissed it as an inferior work. It's certainly a pretty turgid read, crammed with long-winded exposition and with a non-linear timeline that annoyingly gives away all the best plot twists too soon. I felt like scrawling "Spoiler Alert!" in the margins when I wasn't skipping the endless inventories of titles, ranks and possessions of the English aristocracy. But while I was often infuriated by the book's structure I found myself gripped by the underlying story. Here was a truly enthralling tale of love and humanity, of ordinary people struggling to survive in an unjust and unequal society. At it's core is the story of a young man who is kidnapped, mutilated and sold to travelling entertainers, yet who retains his integrity and his dignity through the love of his adoptive 'family', the eccentric philosopher Ursus, his pet wolf Homo and the beautiful blind girl, Dea.

The book is a political thriller, a "whodunit" mystery, a love story and a scathing attack on injustice and social inequality. When, near the story's climax, Gwynplaine addresses the House of Lords, his bitter rebuke of the élite who govern Britain rings as true today as it did then. He launches an assault on this tiny minority who posses most of the wealth and land and all of the power, exploiting the labor of the poor in order to live in luxury, raising taxes to support a parasitic monarchy and treating the common people with contempt. Gwynplaine holds himself up as a symbol of abuse. "I represent humanity, such as its masters have made it. Mankind is mutilated." And he has a warning that one day the people will rise up and restore the Republic that briefly existed under Cromwell.

Victor Hugo would no doubt be appalled that modern Britain remains a monarchy and even more so that the inequality he railed against is still there. In 2014 the richest 1% own as much as the poorest 55% and the wealth gap is growing. That makes The Man Who Laughs as pertinent to modern readers as it was in 1869 when it was first published and the elements of the book that provoked ridicule when it was first published no longer seem as absurd. The grotesque and theatrical settings and characters are more familiar to us today after a century that gave us surrealism, expressionist cinema and the modern gothic imagery of TV shows like Twin Peaks and indeed, the more recent Batman films.

Hugo was an accomplished and visionary artist in his own right and many of the scenes in the book are so well visualized that they played out in my head like a movie. As I read the early scene where the young Gwynplaine is abandoned to walk barefoot through a snowstorm, encountering first a rotting corpse hanging from a gibbet and then, having never been shown a single act of kindness, risking his life to save a child who is even more helpless than himself, I knew I had to turn this into a graphic novel, to bring that story to life and introduce it to a new audience.

A graphic novel is, in many ways, superior to cinema as an art form. Watching a movie is a largely passive entertainment, where sounds and images flow at their own speed. Reading a graphic novel is a much more interactive and intimate experience. The words and images are printed, static, to be read and absorbed at the readers own pace. You can go back and re-read dialogue or pause and study a picture to appreciate the nuances that you didn't pick up first time around.

As a writer I have to know when to shut up and let the pictures do the talking. My collaborator, the artist Mark Stafford has done a real service to the book and I'm sure Victor Hugo would have approved of the way Mark has gotten to the heart of Gwynplaine and the cast of heroes, villains and those 'common' people who are, for the most part neither hero nor villain. If we have done our job right, they will make you laugh and make you weep... and maybe, unless you happen to be part of that privileged 1%, also provoke a little righteous anger.

Read an excerpt from The Man Who Laughs below:

David Hine is the illustrator of a graphic novel adaptation of Victor Hugo's The Man Who Laughs.