It's the kind of thing you probably missed over Thanksgiving dinner, while gnawing on a turkey leg, bickering with your uncle, or falling asleep during a Detroit Lions game: The Miami Marlins just signed an outfielder to a $325 million deal, the largest contract in sports history.

You read that correctly: $325 million. That's Hunger Games money, Transformers money. It's the kind of figure you associate with World Bank loans or Rolling Stone comeback tours. Apple needs at least a day to make that kind of cash.

The young outfielder, named Giancarlo Stanton -- no, I hadn't heard of him, either -- apparently hit .288 with 37 home runs last season. (Note to Marlins: Those were roughly my numbers playing T-ball in 5th grade.) Stanton later celebrated his deal in a Miami nightclub with a $20,000 bottle of champagne coated in 22-carat gold leaf. I don't know whether he kept the bottle.

It says something about baseball today that a guy you've never heard of - again, he plays for the Marlins -- can be signed for $25 million per year over 13 years. Frankly, it's probably a bad deal for the Marlins -- especially if the names Albert Pujols, Alex Rodriguez or Josh Hamilton ring a bell. Players paid more than they're worth - more than some national economies are worth -- rarely stay motivated purely by love of the game.

Love of the game. That's what sports are supposed to be about, isn't it?

When you think about love of the game, you think of Lou Gehrig -- the Iron Horse -- playing in 2,130 straight games until his body gave out from ALS. Or Pete Rose, aka Charlie Hustle, barreling over Ray Fosse in the 1970 All Star game to secure a seemingly meaningless win. Or Kirk Gibson, gamely limping around the bases after hitting his clutch home run in the 1988 World Series.

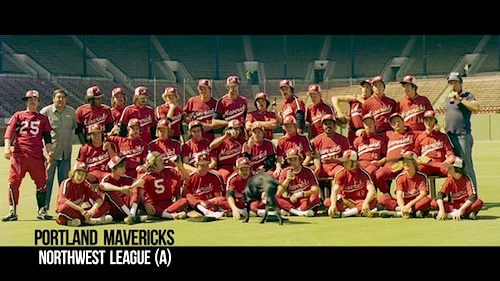

And you should also think of the Portland Mavericks, the subject of a wonderful new documentary called The Battered Bastards of Baseball that premiered this past year at Sundance and is currently showing on Netflix.

We caught Battered Bastards at Sundance and also at this year's Los Angeles Film Festival. At the Sundance screening we had the chance to speak to Kurt Russell, who's interviewed in the film, along with his nephews Chapman Way and Maclain Way, Battered Bastards' co-directors.

The Mavericks -- an independent, Class A minor league baseball team between 1973-77- - were the brainchild of Bing Russell, the actor best known for playing deputy sheriff Clem on TV's Bonanza. A hugely colorful showman with a fast wit ("I played Clem for 13 years on Bonanza and never solved a case"), Russell appeared in countless film and TV westerns, and made a career of getting killed on camera -- most notably in Howard Hawks' Rio Bravo and John Ford's The Horse Soldiers.

Of course, Russell is best known today as the father of Kurt Russell, who himself played for the Mavericks in 1973.

As Battered Bastards relates, Bing served as a bat boy for the mighty New York Yankees between 1936-41, when he got to know legends of the game like Joe DiMaggio, Lefty Gomez and Lou Gehrig (who gave young Bing his bat after hitting the final home run of his storied career). Although Bing later tried his hand at pro baseball, an injury cut short his career -- leading him to try an acting career in Hollywood.

His love of baseball never left him, however -- so when his acting career stalled in the early 1970s, Russell jumped at the opportunity to bring pro baseball to Portland in 1973 after the prior team left town.

"Baseball was a big part of our family," Maclain Way told us. "Kurt, our uncle, played professional baseball. Bing, himself, played professional baseball. We had cousins who played major league baseball, so baseball was a huge part of our life growing up. I played baseball in high school because of Bing -- he taught me how to play."

The upstart Mavericks would become a team like no one had seen before -- totally unaffiliated with any big league franchise, and filled to the brim with misfits and rejects -- a scrappy, real life Bad News Bears squad.

"He had a great eye for ball players," Kurt Russell told us, speaking warmly of his father. "We knew we could put a competitive team together."

Managed by restaurant owner Frank "The Flake" Peters, the Mavericks' roster of wild characters would include: a shaggy, 33 year-old high school English teacher named Larry Colton (who'd later be nominated for a Pulitzer Prize); 38-year-old ex-Yankee Jim "Bulldog" Bouton (who'd been blackballed from baseball after writing a wild tell-all memoir); Joe Garza (aka "JoGarza"), a madman utility player who waved flaming brooms when the Mavericks swept opposing teams; Rob Nelson, who invented Big League Chew bubble gum in the Mavericks' bullpen; star outfielder Reggie Thomas, who took a limo to games even though he lived only a block from the stadium; and fiery batboy Todd Field, who once got tossed from a game, and later became an Academy Award-nominated writer-director.

And, of course, there was Kurt Russell. "I got injured [playing minor league baseball in Texas], so I had the opportunity to go to Portland and help them get the ball club started," Russell told us.

"It was just a time in my Dad's life where I was really happy he was involving himself in something completely new," says Russell. "It was a big part of our lives."

The Mavericks were also a team of firsts, boasting baseball's first female general manager (Lanny Moss), first Asian general manager (Jon Yoshiwara), a leftie catcher named Jim "Swannie" Swanson, a ball girl, even a ball dog named "P.L. Maverick."

A sucker for hard luck cases, or outsiders looking for a second chance, Bing Russell surrounded himself with baseball's colorful cast-offs - the people nobody else wanted. "You never know who's going to come up with that magic moment," he said.

Or as former Yankee cast-off Jim Bouton put it, "our motivation was simple: revenge."

Built around speed and reckless play, the Mavericks were initially looked upon as a joke - until Mavericks pitcher Gene Lanthorn threw a no-hitter in the team's first game, and it was off to the races. The Mavericks proceeded to clobber their competition and set attendance records, becoming overnight media sensations covered by NBC, Sports Illustrated - even The New Yorker.

With a roster of ragamuffin players culled from open, public tryouts, the Mavericks shocked the baseball world in 1977 by achieving the highest winning percentage of any team at any level of the game (.667). The Mavericks became the team nobody wanted to play - a cocky, hard-partying Wild Bunch that regularly whipped squads boasting future major leaguers like Ozzie Smith, Dave Henderson, Dave Stewart or Mike Scioscia.

For this, incidentally, players were paid $400 a month.

Fun as the Mavericks were, they were completely serious about winning. "It wasn't a hobby, it wasn't a lark - it was very important," Russell told us. "We were good at baseball."

The Mavericks played like they had nothing to lose, and fans loved them - but the baseball establishment didn't. Nobody likes being upstaged, and the Mavericks were upstaging everyone - making Major League Baseball's product look bad.

The league's solution was simple: put the Mavericks in their place. On the verge of winning their first pennant in 1977, the Mavericks lost a quasi-rigged title series playing against talent culled from upper level AAA squads. Mavericks batters were repeatedly beaned, and the team lost in the championship game, 4-2.

Shortly thereafter, Major League Baseball jammed a replacement team into Portland - effectively putting the Mavericks out of business.

Not to be outdone, Bing Russell would get his revenge, however - winning a groundbreaking lawsuit against the Pacific Coast League that paved the way for independent baseball's return.

"It's the American Dream," as Russell put it. "It's a matter of opportunity, not the almighty dollar."

The Battered Bastards of Baseball is currently being adapted into a feature narrative by producer Justin Lin and Todd Field - and it's not hard to understand why. As told in the documentary, Bing Russell's story is similar to those of Preston Tucker or Steve Wozniak - eccentric American visionaries who fought the system and won, paving the way for dreamers to come.

"He was a very capable man," says Kurt Russell. "My Dad was a business grad out of Dartmouth, and he became an actor, and before that he was a baseball player," his famous son told us. "He kind of put all three of those things together."

"My Dad was a very, very independent-minded guy," Russell says. "He lived life his way."

Bing Russell's legacy clearly lives on today - mostly notably in his son and grandsons. "Let's face it, you are a lot of what you learned from your mother and father from the first day forward," Kurt Russell told us. "And then, as your life continues on, you find yourself sounding more and more like your parents," laughs Russell.

What young Kurt took from playing with the Mavericks were "a lot of lessons in entertainment, business, baseball."

"I carried with me what my Mom and Dad had created."

"Bing took a shot at something that nobody else wanted to do," says co-director Chapman Way, Russell's grandson. "He started this independent baseball team - this kind of David versus Goliath story. He really followed his passions and followed his dreams, even when other people thought, 'there's no way this could work.'"

"He still put it together, and went up there and did it," Way told us. "And I think that's really admirable, and something that I'm really proud of."

Russell's family is hardly alone in thinking this - as many ex-players and Portlanders interviewed in the documentary barely hold back tears discussing the late Mavericks' owner. The heart and soul of the Portland Mavericks, Bing Russell comes across as an inspiring, Capra-esque figure - a big-hearted, fast-talking impresario who made great things possible for other people.

While always putting on a good show.

"He loved to make things happen for people to enjoy. That was what drove my Dad," says Kurt Russell of his father. "And I guess I got that bug."

The Mavericks' story is the kind that's hard to resist during the holiday season, especially as pro and college football ramp up to their end-of-the-year commercial onslaught, a slick corporate stage show with billions of dollars at stake. Even college sports seem hopelessly venal at this point, long past the point of no return.

Under the smart, assured direction of Chapman and Maclain Way, and featuring a wistful score from Brocker Way, The Battered Bastards of Baseball tells a different kind of story: an emotional, rough-and-tumble tale of pursuing the American Dream - purely for love of the game, even when you don't have two wooden nickels to rub together.

Let alone wooden nickels coated in 22-carat gold leaf.