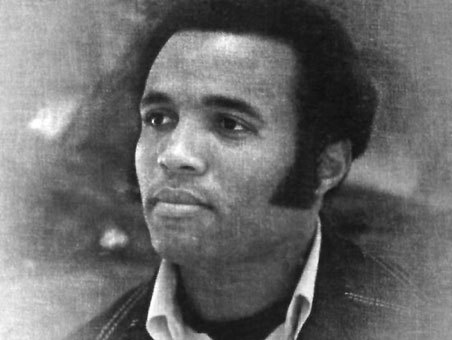

"Now he belongs to the ages," was my first thought when I got the call that my friend Andraé Crouch had succumbed to the heart attack that felled him the week before. That most famous epitaph in history originally belonged to Edwin Stanton describing the passing of Abraham Lincoln and as grandiose as it may sound, in musical terms, Crouch'a passing is on par with Lincoln's, for he was a musical giant who may one day be fully appreciated in death in ways that sometimes eluded him in life.

There are reasons his musical genius may not have been understood in his lifetime and one of them is no doubt the genre in which he operated for most of his career, Gospel, as well as the fact that he never hesitated to take a pass on participating in projects that he felt would compromise his beliefs.

No less an icon than Madonna found this out the hard way when in 1988 at the peak of her fame, she turned to Crouch for help on a song "Like A Prayer," and Crouch and his choir obliged with a command performance that gave the song power, emotion and depth. But when she sang "let the choir sing" leading into Crouch's performance, she likely had no clue that he would later politely decline when it came time to film the video for the track. The reason: Madonna had chosen to take the video in a different direction than the song and Crouch wanting no part of a video that sexualized images of saints who came to life, left Madonna no choice but to dress others up in choir robes and have them do their best Milli Vanilli. As he told me matter-of-factly years later, "the video was something I didn't believe in."

"What did she say?" I prodded.

"She said, 'I understand,'" he replied.

Life is a mystery, everyone must stand alone, indeed.

Crouch recalled the story without a hint of bitterness or disappointment, but one can only imagine the limitations that would naturally follow for an artist who was willing to walk away from career-making opportunities like that one and they no doubt affected his ability to reach a mass audience beyond the Gospel genre.

There's also the fact that when we think of great singer/songwriters it is rock/pop artists like Billy Joel, Joni Mitchell, James Taylor, John and Paul and Taupin and Elton that come to mind and not Gospel artists.

But a strong case can be made that Crouch belongs in that select group of singer/songwriters for the combination of his vocal performance, raw songwriting talent and piano playing.

Crouch was an imaginative songwriter whose lyrics were unusually personal, and he was fond of quoting others talking to him ("they say Andraé how can you have a song when everything is going wrong"), imagining how God talked to his arch-nemesis, ("they're gonna keep on living for me Satan, they're not gonna turn around,") quoting Old Scratch talking to him ("Satan tried to tell me 'Andraé why don't you just throw in the towel,'") and even imagining how his mother talked to God ("I heard her say 'help Andraé , Lord Jesus, keep him close to your heart.")

There was also his trailblazing work in bringing sounds that traditionally appealed primarily to African-Americans, to a white audience, for while mainstream audiences in the '50's needed the likes of Elvis and Pat Boone to bring R&B rhythms to them, Crouch needed no such translators and was warmly received by white audiences for most of his career. But, it's important to note, that didn't just happen, for Crouch carefully and methodically wooed white audiences, he later recalled:

"My Father had told me 'Andraé a lot of people don't like black Gospel music because they think they can't understand the words.' So he said, 'Why don't you always give people two chances to hear what you're saying, to understand what you're saying.' So when we would sing 'through it all,' I'd go 'through it all through it all, I've learned to trust in Jesus, oh I've learned to trust in God.' And when you do that they'll catch one of them," Crouch added with a laugh.

And just as his Father predicted, white audiences adored Crouch's music and many of his songs like the first song he ever wrote at the age of 14, "The Blood Will Never Lose Its Power," along with others like "My Tribute," are still sung in churches across the country today.

But as the title of his first album Take The Message Everywhere, would hint at, Crouch's early music with its strong soul and occasional funk elements was begging to be liberated from the four walls of the church and even in his early days he was clearly paying attention to what was happening outside of the Gospel world. Seven years after the Rolling Stones first expressed the complaints of a generation fed up with various social ills in "I Can't Get No Satisfaction," Crouch offered a soul/funk response with "Satisfied," declaring that he was "Satisfied with Jesus."

But beginning in 1979 he began a serious attempt to take his music into the musical mainstream with a record entitled "I'll Be Thinking Of You," which was distributed by Elektra and featured an all-star cast of players that included Stevie Wonder, Philip Bailey of Earth, Wind & Fire, Joe Sample and others.

In 1981, Crouch took his mainstream moves to the next level, signing with Warner Brothers and releasing "Don't' Give Up," with another cast of all-star musical talent that included members of Toto, and The Brothers Johnson. Despite his new label home, Crouch could hardly be accused of toning down his message, beginning the record with the smooth "Waiting For The Son," the urgent Gospel message of "I Can't Keep It To Myself," the spiritual "I Love Walking With You," and even an anti-abortion number, "I'll Be Good To You Baby" which in case the message was missed was subtitled "A Message To The Silent Victims."

Not everybody in the church world was supportive however and in successive years Crouch transitioned to working on films like The Color Purple, The Lion King, Free Willy and others performed background vocals for the likes of Michael Jackson and Madonna and released sporadic comeback albums that never quite reached the heights of his work in the '70s and early '80s. When his parents and brother passed away, Crouch took on the additional responsibilities of pastoring his family's church and would spend the last two decades of his life leading New Christ Memorial Church where he could be found most Sundays singing and leading the services with this twin sister Sandra, who was faithfully by his side throughout his career.

Mainstream critics who have long ignored Crouch will have plenty of time to re-evaluate his work and the contributions he made not just to the bridging of the chasm that has, thanks to the likes of Sam Cooke, Robert Johnson and others, separated Gospel from the rest of the music industry, but also to the uniting of the races, black white, yellow and brown who all found something in his music (Crouch regularly toured Europe and had a following in Asia.)

But Andraé Crouch the artist may for some remain something of an enigma for he came to his craft with little in the way of formal training, insisting that his musical gifts came from God and only after his father had laid hands on his son and asked that musical talent be divinely given to him, and for the purpose of spreading the Gospel message. Crouch took that charge seriously:

"For me that's what it's all about. We're here to win souls," he once told me. "When he uses me to win the last one, I'm out of here. Until then, all you're going to hear from us is how can we win that person to Jesus Christ. I don't even want to think I know a person that went to hell. I don't even want to think that our paths crossed and they ended up in hell."

In 1975, with his tried and true method of repeating himself to make sure nobody missed his message, Crouch laid out his vision of what he might one day consider a successful life in the song, "I'll Still Love You:"

Even when the cold winds blow, dear Lord I want you to know, I'll still love you Lord, I'll still love you. Even if I stumble and fall, my friends don't answer my call, even if I never reach fame and people don't remember my name, even when I'm old and gray and find it hard to see my way, I'll still love you, Lord I'll still love you.